sculpture

Big Rosa (THE PRINCESS – THE PRINCE – THE ARTIST'S TROUSERS)

- MARMOR, Kunsten - Museum of Modern Art Aalborg, 2022

- Poul Gernes: Jeg kan ikke alene - vil du være med?, Louisiana Museum for Moderne Kunst, 2016

- Invitation til en kop mælk - og alt godt fra Poul Gernes, Nordjyllands Kunstmuseum (Kunsten Museum of Modern Art Aalborg), 2001

- Serier af Poul Gernes, Clausholm Slot, 1996

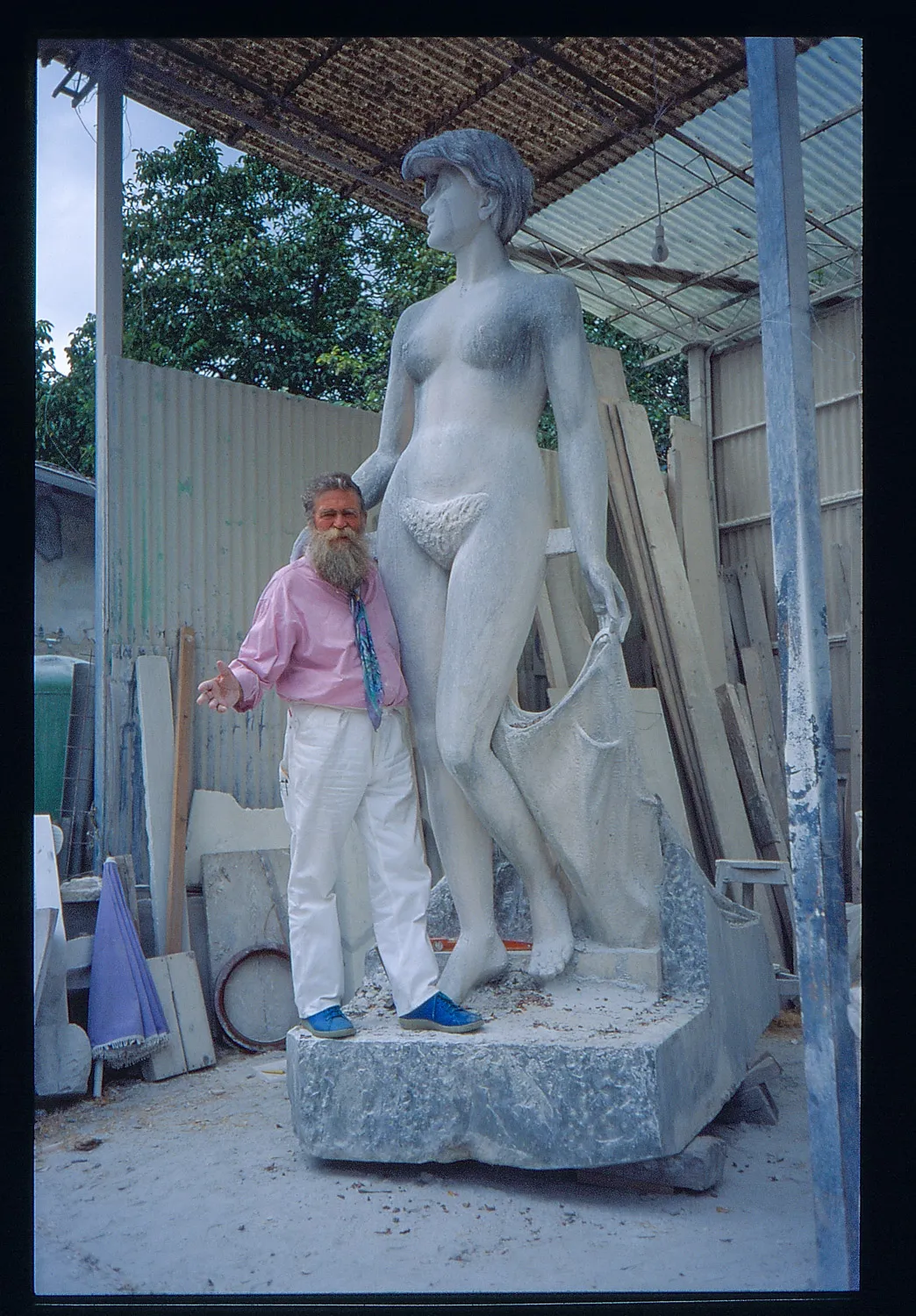

In the spring of 1980, the Gernes family loaded their Volvo Duett and drove from their home and studio in northern Skåne to the stone carving town of Pietrasanta in northwestern ltaly. In the car was a mannequin, modified by Poul Gernes and intended to serve as model for the two figurative stone sculptures in Gernes' comprehensive work Big Rosa and Little Rosa. During the years that followed, Gernes made several trips between Skåne and Pietrasanta, but during that time he also began to devote more time and energy to public commissions in Denmark. As a result, the sculptures in ltaly were never fully finished but were left standing in the stone studio.

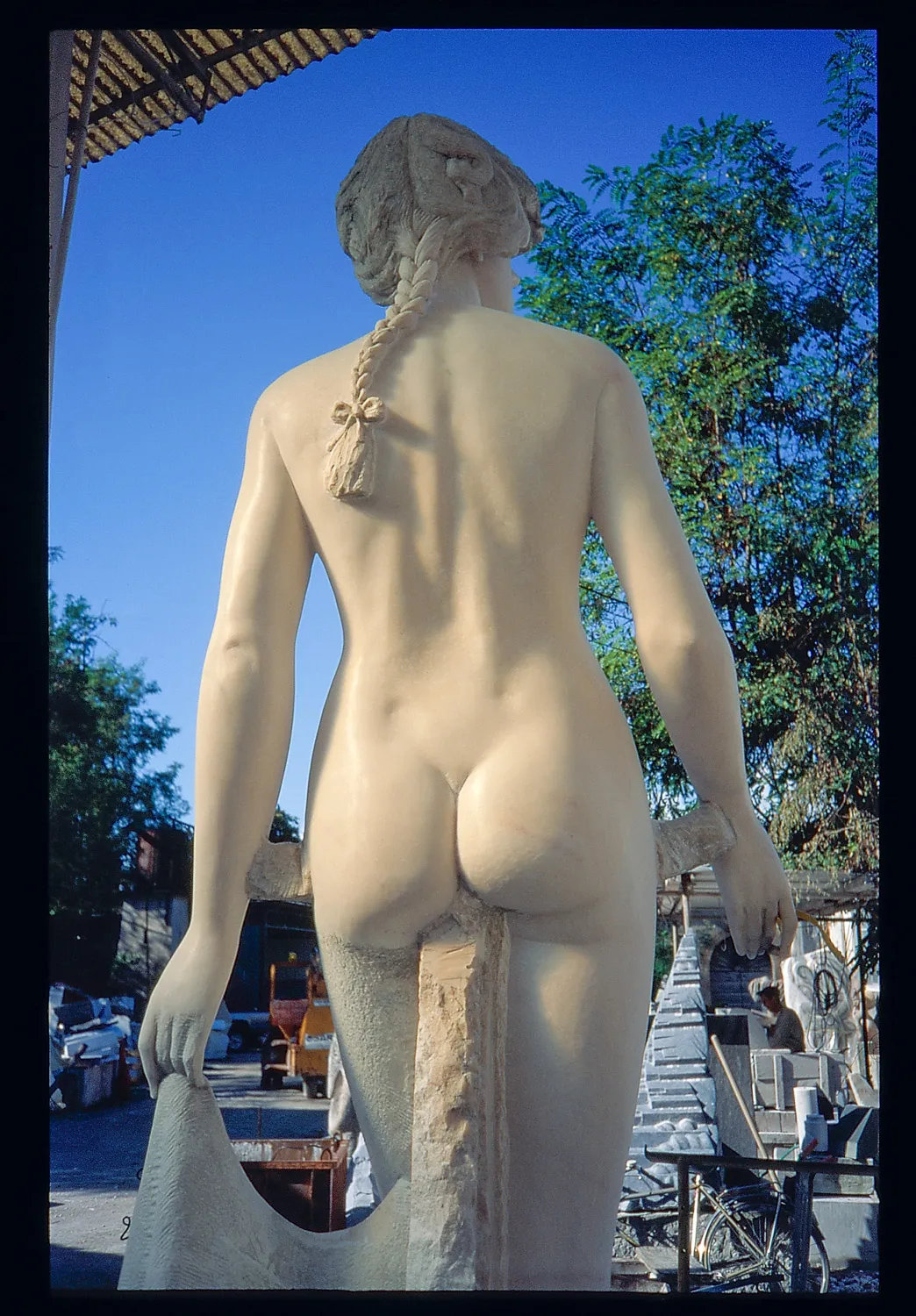

Fifteen years later he felt the need to finish the sculptures, and in the summer of 1995, I accompanied Poul and Aase Gernes to Pietrasanta to assist in the completion of the Rosa sculptures. The two sculptures, with their archaic, silent faces and stylized stone bodies, were waiting for us in the famous stone studio of Sem Gherlardini. Many years under the open Italian sky had left a dark and uneven surface layer on the face of the rose-colored Portuguese marble. Our task was to finish the sculptures: to carve the final details; incorporate ornamental leaves in the stone of Little Rosa's plinth; decide on the precise shape of the decorative hair and to cut and polish the surface layer of Big Rosa.

It is actually two versions of the same sculpture in different scale. Little Rosa is cut from a single bloc of marble, a thing that may be hard for the untrained eye to see since the step formation of the plinth covered by an inlay of winding leaves – ornamentation often found decorating the wall of Gernes numerous public commissions.

Big Rosa consists of two kinds of stone. The figure is – as in the case of Little Rosa – of rose-colored Portuguese marble, while the plinth is carved from gray ltalian marble. Both Rosa figures hold pair of work pants of the type favored by Poul Gernes in their left hand. The pants fall toward the plinth in soft drapes, serving as support for the tall stone body and as a gesture to the traditional draping of the classical figurative stone sculptures.

Characteristic for Gernes is that his sculptures embrace a large span of art history – from antique sculpture via Duchamp's Nude descending a staircase to sixties Pop Art. The modified mannequin that served as model for the sculptures has lent them a stylized look, free from any naturalistic ambition. Their expressively abundant hair serves a special function. Gernes did not want the character of the sculptures to suggest a specific style or epoch, so he gave them a very distinct, ornate hairstyle, if anything reminiscent of the freely undulating forms of the Baroque.

Many have pointed out that the heads of both sculptures bear a strong resemblance to the young Aase Gernes, so the broad historical span of the sculptures probably includes a very personal reference. On the plinth of Big Rosa there is a little frog, it, too, carved out of marble, and on the side of the gray plinth is an inscription in Danish which in English reads: THE PRINCESS, THE PRINCE, AND THE ARTIST'S PANTS.

Working with a figurative marble sculpture is a very slow process, and the farther along toward the finished sculpture, the slower it is. It is a matter of infinitesimal differences: the way light falls on the surface of the stone, the way shadows define a concave or convex form. Sometimes the eye is unable to decide, that is when the sensitivity of the fingertips takes over – they are able to discern nuances, differences in level and details which the eye is incapable of registering. A stone sculpture has a long and reliable memory. It can be left, incomplete, in a studio for fifteen years, only to be awakened to life again, and work can resume exactly where it left off. To a sculpture, carved in stone millions of years old, fifteen years is only the twinkling of an eye.

Much had happened in the world during these fifteen years. The Berlin wall had come down and the digital revolution had initiated its comprehensive transformation of human communication. The Rosa sculptures were literally anachronisms already when Gernes began work on them, something outside the order of the linear notion of time. It was precisely this that was Gernes' ambition, however: to create timeless pieces that could not be ascribed to a specific genre or be reduced to a specific artistic style.

Gernes had originally planned to color the eyes, lips and cheeks of the two Rosa sculptures, the way that ancient Greek marble statues had been painted in bright colors, but he did not have the time. Big Rosa was Poul Gernes’ last work. In March of 1996, shortly after his return from Pietrasanta, Poul Gernes died – only a few days before the Rosa sculptures were to be shown for the first time at an exhibition in Denmark.

To work on a stone sculpture is a concrete way to allow your thoughts to leave traces in matter, to transform an idea into form through a continual negotiation process with the will of the stone. It calls for experience as well as patience. The nature of the final phase of the work, the polishing of the surface, is special and almost intimate. It is body against body, living skin against the surface of the stone, with nothing but a thin sandpaper in between. Poul and Aase Gernes polished Little Rosa themselves. It was a slow and tender process, as if caring for a long-lost friend.

Shortly before leaving for Pietrasanta in the summer of 1995, the Gernes family had experienced a great loss. A young member of the family had died in a tragic accident, and sorrow therefore inevitably became their companion on their trip and their stay in ltaly. It is impossible to leave that kind of sorrow behind when you go to work. Sorrow went with them to the studio; it mingled with the stone dust, whirled in the air, and settled like a fine, thin coat over everything and everybody.

The work on finishing the sculptures may have been a way of getting through the initial difficult period in the inexorable dramaturgy of mourning. To have a daily task, a job that has to be done, something to keep the body busy while allowing your thoughts time to get accustomed to the unthinkable. That was probably how it was, those months in Pietrasanta. Ars longa, vita brevis.

Anders Krüger: “On the memory of stone.” In: Poul Gernes / Sidekick / Cosima von Bonin. Stockholm, Artipelag Konsthall 2013. Translated from Swedish “Om stenens minne” by Dan A. Marmorstein. Abbreviated.

Big Rosa (THE PRINCESS – THE PRINCE – THE ARTIST'S TROUSERS)

Photo: Anders Krüger

Big Rosa (THE PRINCESS – THE PRINCE – THE ARTIST'S TROUSERS)

Pietrasanta 1995

Photo: Anders Krüger

Big Rosa (THE PRINCESS – THE PRINCE – THE ARTIST'S TROUSERS)

Pietrasanta 1995

Photo: Anders Krüger

Big Rosa (THE PRINCESS – THE PRINCE – THE ARTIST'S TROUSERS)

Pietrasanta 1995

Photo: Anders Krüger

Big Rosa (THE PRINCESS – THE PRINCE – THE ARTIST'S TROUSERS)

Pietrasanta 1995

Photo: Anders Krüger

Big Rosa (THE PRINCESS – THE PRINCE – THE ARTIST'S TROUSERS)

Clausholm Slot 1996

Photo: Ulrikka Gernes

Big Rosa (THE PRINCESS – THE PRINCE – THE ARTIST'S TROUSERS)

Aase Seidler Gernes and Big Rosa, Clausholm Slot 1996

Photo: Jesper Gernes

Big Rosa (THE PRINCESS – THE PRINCE – THE ARTIST'S TROUSERS)

Nordjyllands Kunstmuseum 2001

Photo: Ulrikka Gernes

Big Rosa (THE PRINCESS – THE PRINCE – THE ARTIST'S TROUSERS)

Louisiana Museum of Modern Art 2016

Photo: Louisiana Museum of Modern Art

Big Rosa (THE PRINCESS – THE PRINCE – THE ARTIST'S TROUSERS)

Kunsten Museum of Modern Art 2022

Photo: Ulrikka Gernes

Big Rosa (THE PRINCESS – THE PRINCE – THE ARTIST'S TROUSERS)

Kunsten Museum of Modern Art 2022

Photo: Ulrikka Gernes

Big Rosa (THE PRINCESS – THE PRINCE – THE ARTIST'S TROUSERS)

Kunsten Museum of Modern Art 2022

Photo: Ulrikka Gernes

Big Rosa (THE PRINCESS – THE PRINCE – THE ARTIST'S TROUSERS)

Kunsten Museum of Modern Art 2022

Photo: Ulrikka Gernes

Big Rosa (THE PRINCESS – THE PRINCE – THE ARTIST'S TROUSERS)

Kunsten Museum of Modern Art 2022

Photo: Ulrikka Gernes

Big Rosa (THE PRINCESS – THE PRINCE – THE ARTIST'S TROUSERS)

Kunsten – Museum of Modern Art 2022

Photo: Ulrikka Gernes

Big Rosa (THE PRINCESS – THE PRINCE – THE ARTIST'S TROUSERS)

Kunsten – Museum of Modern Art 2022

Photo: Ulrikka Gernes

Big Rosa (THE PRINCESS – THE PRINCE – THE ARTIST'S TROUSERS)

Kunsten – Museum of Modern Art 2022

Photo: Ulrikka Gernes

Big Rosa (THE PRINCESS – THE PRINCE – THE ARTIST'S TROUSERS)

Kunsten – Museum of Modern Art 2022

Photo: Ulrikka Gernes